In 2024, Geoffrey Hinton was awarded the Nobel Prize for his contributions to artificial intelligence. A key milestone in his work came in 2012 with AlexNet, a neural network he developed with his students Alex Krizhevsky and Ilya Sutskever, sparking a revolution in AI. But more than a decade earlier, in 2001, Paul Viola and Michael Jones first gave machines the ability to see you in real-time.

Seen in historical context, Viola-Jones is nothing short of a technological sleight of hand. While the individual pieces of its framework—Haar features, cascades, and classifiers—weren’t revolutionary on their own, the brilliance lay in how they were stitched together to outmaneuver the brutal hardware constraints of the early 2000s. It didn’t provide the level of generality of deep neural networks that were to come later, but it did something those networks couldn’t yet dream of: it unlocked real-time face detection, reshaping our interaction with machines. From cameras that automatically framed smiles to surveillance systems quietly scanning the streets, Viola-Jones wasn’t just a step forward—it was the moment machines began truly seeing us.

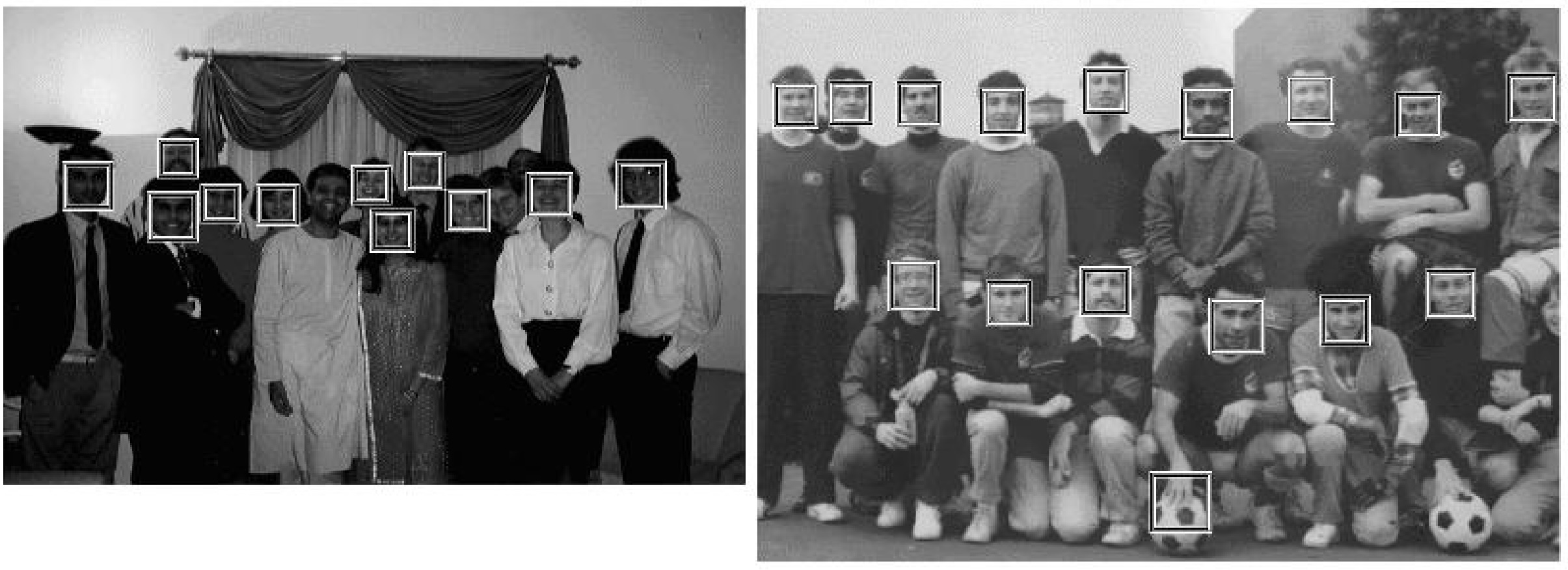

Faces detected by the Viola-Jones algorithm

Faces detected by the Viola-Jones algorithm

A pivotal moment

The Viola-Jones algorithm, as it came to be known, was introduced in the seminal paper “Rapid Object Detection using a Boosted Cascade of Simple Features” at the 2001 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). A mix of academic researchers, industry professionals, and students were eagerly waiting, keenly interested in seeing how this breakthrough could push the boundaries of what computers were able to achieve. Most sitting in that conference room didn’t know at the time that they were witnessing first-hand an inflection point on machine perception. Ten years later, the Viola-Jones paper would be awarded the Longuet-Higgins Prize for most significant contributions to the Computer Vision field in that decade.

The core intuition behind Viola-Jones is that certain facial regions, like the eyes, nose, and mouth, are critical for identifying human faces. In greyscale front-facing images (assuming lighting is balanced), you’ll notice key patterns: the eye-brow region tends to be darker at the top (brows) and lighter below (eyes), while the nose bridge appears brighter compared to the adjacent cheeks.

Haar-like features type 2 and type 3

Haar-like features type 2 and type 3

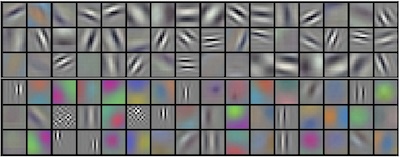

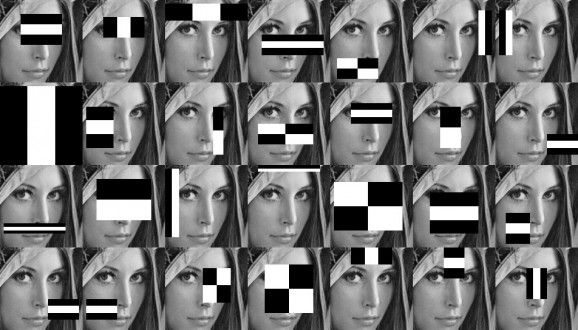

Viola-Jones takes this intuition and encodes it into Haar-like features–simple contrast-based patterns that can capture these facial structures. Reminding you of convulotional neural networks yet? In fact, the algorithm uses around 6,000 Haar features and scans these across small sub-windows (24x24 pixels) throughout the image. Each Haar feature serves as a weak learner, detecting basic patterns, and when combined into an ensemble by running a variation of AdaBoost, a boosted feature learning algorithm, they form an effective classifier.

Convolutions from later deep learning methods

Convolutions from later deep learning methods Both convolutions and Haar-like features detect patterns and edges

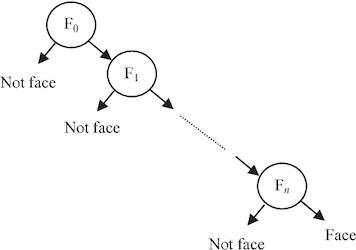

To make the detection fast and scalable, Viola-Jones introduces a cascade of classifiers. Early stages quickly eliminate non-face regions, allowing more computational effort to focus only on promising, face-like areas. This cascading structure ensures the algorithm is both efficient and effective, making real-time face detection possible.

Cascading logic used by Viola-Jones to quickly discard non-face regions

Cascading logic used by Viola-Jones to quickly discard non-face regions

Its versatility and efficiency established Viola-Jones as a foundational technology that significantly shaped the landscape of machine vision in everyday devices.

The human brain

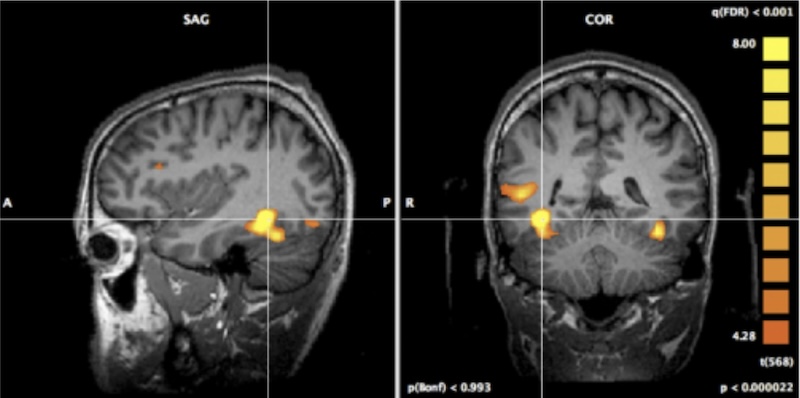

The human brain identifies faces primarily through the Fusiform Face Area (FFA), a specialized region in the temporal lobe responsible for processing faces holistically. Rather than breaking a face into individual parts (like just the eyes or mouth), the FFA recognizes the entire face as a unified whole.

Highlight of the FFA region of the human brain

Highlight of the FFA region of the human brain

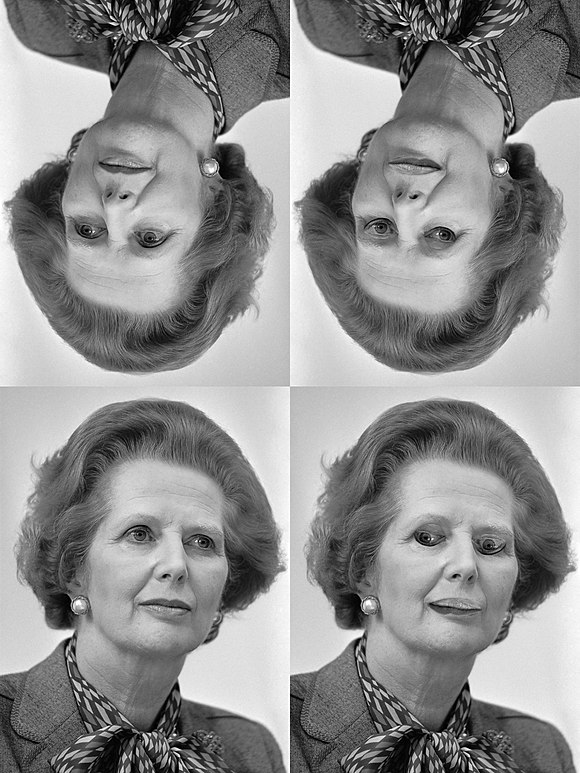

This holistic perception explains the Thatcher Effect, where flipping only the eyes and mouth in an upside-down face makes it look relatively normal—but when viewed upright, the distortion becomes jarringly obvious. This suggests that our brains struggle to process faces correctly when they’re misaligned because we rely on seeing them in their full, integrated form.

The Thatcher effect

The Thatcher effect

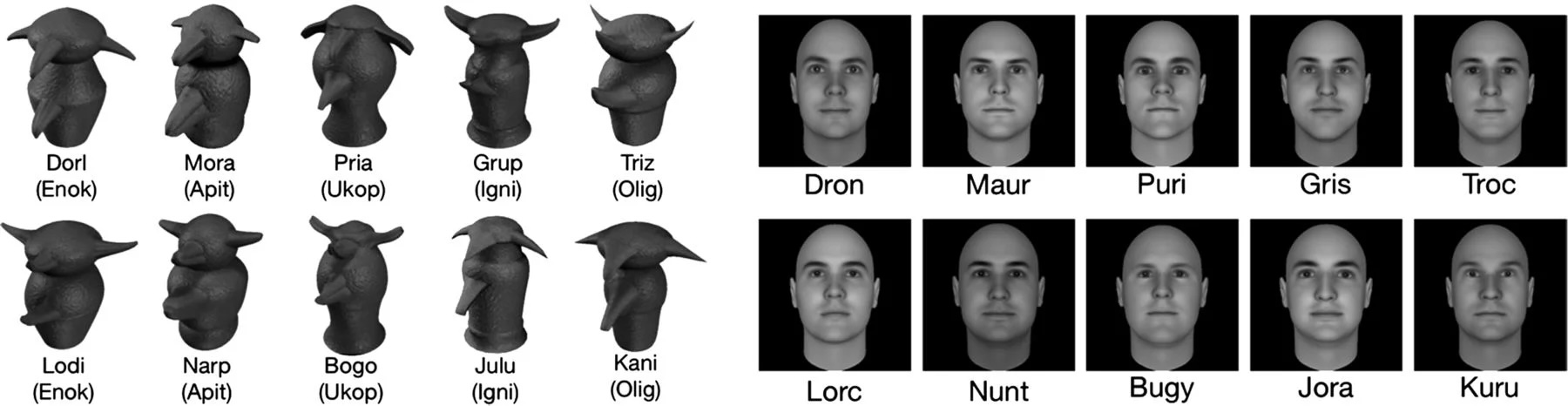

To explore this ability, scientists created the Greebles test—a study that exposes participants to strange, face-like objects called Greebles. Initially, participants struggle to differentiate between Greebles, but with training, they develop a more specialized way of recognizing them, indicating that the FFA can adapt to learn new categories of visual expertise, not just human faces.

Greebles used for testing the ability of the FFA region to understand more than faces

Greebles used for testing the ability of the FFA region to understand more than faces

In contrast, as revised above, Haar features, used in the Viola-Jones algorithm, take the opposite approach. They analyze faces in a piecewise manner by detecting simple patterns. This method allowed for early real-time face detection on low-power devices, but it lacked the holistic capacity seen in the FFA, making it prone to errors when encountering complex angles or lighting conditions that humans would easily overcome.

This limitation foreshadowed the need for more sophisticated methods, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which mimic the brain’s hierarchical way of learning. CNNs don’t rely on hand-crafted features like Haar patterns but instead learn directly from vast datasets. Early layers of CNNs detect edges and textures, similar to Haar features, but deeper layers build complex, abstract representations of objects—just as the FFA captures the entirety of a face. This transition from manually designed features to data-driven learning revolutionized computer vision, allowing machines to not only detect but also understand faces with near-human precision, paving the way for modern facial recognition systems powered by deep neural networks.

Deep neural networks revolution

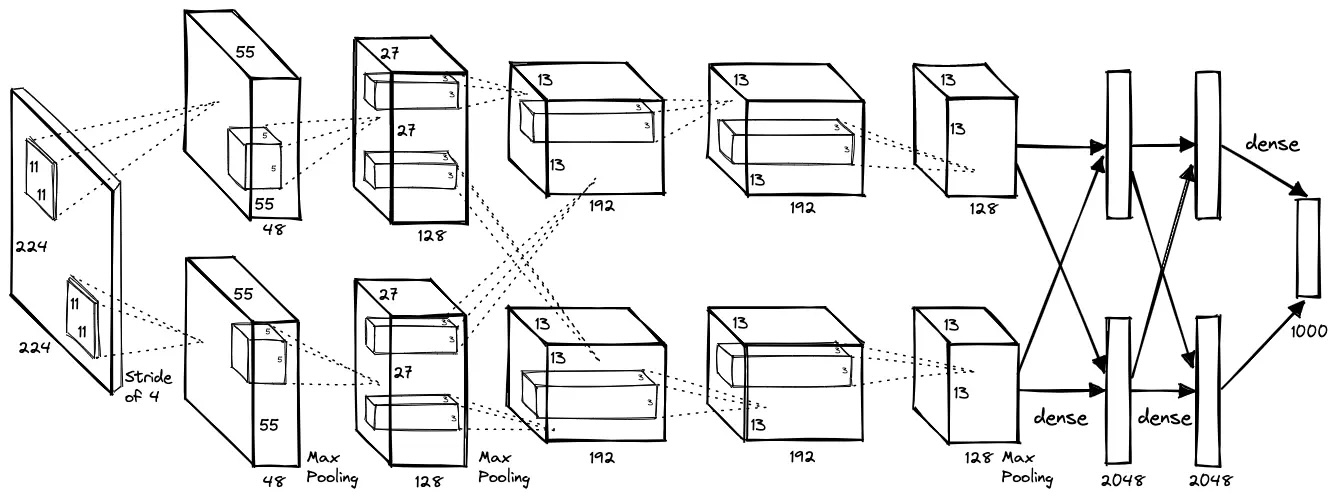

In 2012, the SuperVision team, made up of 3 Canadian academic researchers submitted their contender model AlexNet to try and beat the competition on the ImageNet benchmark. Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever and Geoffrey Hinton completely aced the test and beat the runner up by more than 10%. The formula to it? Deep neural networks trained on GPUs.

AlexNet, the neural network that changed AI forever

AlexNet, the neural network that changed AI forever

NVIDIA GeForce GTX 580 GPU

NVIDIA GeForce GTX 580 GPU

Another deep neural network-related Nobel laureat was announced in the same year as Geoffrey Hinton. Demis Hassabis, founder of Deepmind–developers of AlphaGo–won the Nobel prize in Chemistry for AlphaFold.

The elephant in the room of this essay is Yann LeCun and his LeNet-1 model, which goes as far back as 1989. It was never applied to face detection with the same level of success as other deep neural networks, mainly due to computational resource constraints at the time. Only in the 2010s did neural networks get applied to faces in real-time scenarios (MTCNN, BlazeFace, etc.). Still, his work and that of Yoshua Bengio were some of the most premonitory in the field, and it served to influence an entire industry.

Today Geoffrey Hinton, Yann LeCun and Yoshua Bengio are considered the godfathers of the AI revolution.

Paul Viola is currently a Distinguished Engineer at Microsoft, after having led Amazon Prime Air robotics and drone technology. Michael Jones is a Senior Principal Research Scientist at Mitsubishi Electric Research Laboratories, researching the explainability of deep neural networks.

Paul Viola and Michael Jones

Paul Viola and Michael Jones

Lenna and her Haar features

Lenna and her Haar features