During early Ancient Greece (400s BC), whilst Hippocrates pioneered medicine and particularly skin disease categorisation, psoriasis (“psora”, for “itch”) and lepra (“lopos”, for “epidermis”) were often conflated. Much later during the Roman empire, another medical encyclopaedist by the name of Aulus Cornelius Celsus would go on to describe the skin condition and conflate it this time with impetigo, but still charaterise it by its tell tale signs to the human eye: “red skin covered with scales.”

Dr. Thomas Fitzpatrick

Dr. Thomas Fitzpatrick

Some 2000 years later, Thomas Fitzpatrick was born. And with him, medicine would be changed forever. Fascinated by skin as an organ, Dr. Fitzpatrick is hailed as the father of modern dermatology. He would go on to develop PUVA treatment to combat psoriases and other skin disorders. As part of PUVA, he created what is known today as the Fitzpatrick scale of human skin phototypes. It described initially four and later six different skin tones by their level of ability to burn or tan. Put more technically, it is used to estimate the response of your skin type to UV (ultraviolet) light:

Fitzpatrick scale

Fitzpatrick scale

Dr. Fitzpatrick went on to develop some of the early modern sunscreens and his Fitzpatrick scale would most recently be used to create diverse and inclusive emoji modifiers to depict different human skin tones (instead of the standard universal smiley face yellow), with the five modifiers being a direct mapping of it, with types I and II merged together.

Emoji modifiers based on the Fitzpatrick scale

Emoji modifiers based on the Fitzpatrick scale

Different forms of categorising human skin tones have existed and they have been applied as part of different scientific studies. Research about socio-economic impact of skin tone (fairness, opportunity), others around anthropology and diversity across geographic areas. All of the proposed methods seem very much flawed from the get go, though. They all depend on subjective measurements that are bottlenecked by the human ability to distinguish skin tones or colors under a specific environment (e.g., dawn, day light, evening). In that regard, nothing beats the scientific accuracy of something like spectrophotometry.

As machine learning and AI models were growing in adoption, questions around fairness and bias started to arise (2015). Early research focused on the well-established Fitzpatrick scale of six categories to stratify human skin tone, as that was at the time deemed a good enough proxy. Gender Shades (2017) and other studies surfaced consistent issues, particularly on darker skin tones. E.g., women with type VI Fitzpatrick skin tone were incorrectly gendered by AI/ML systems in almost 50% of the cases, “the chances (…) of being correctly gendered [come] close to a coin toss”.

Google’s response to the need for something better was the Monk Skin Tone Scale. In 2019, Dr. Ellis Monk partnered with Google to develop a new scale comprised of 10 different skin tones with the intention of having “an inclusive skin tone scale.”

Monk Skin Tone Scale

Monk Skin Tone Scale

Data set construction, data annotation, and, ultimately, the algorithms that flow from these processes in facial recognition software, self-driving cars recogntion of their environments, automatic image classification in photos and videos (e.g., skin tone classification, gender classification, etc.), and more, are all vulnerable to biases when the standard of measurement for skin tone is not as inclusive as it could or should be.

Dr. Monk hits it right in the nail, going into detail of how models are trained and the influence of the quality of (ideally diverse) datasets on the final byproduct of such training, i.e., the model:

For example, lack of comprehensive and diverse training data sets (in terms of race and skin tone) is one leading explanation for facial recognition inaccuracies (e.g., spurious matches) and inaccuracies in automated, machine-learning driven image and video classifiers. In short, similar issues plague both pulse oximetry and machine learning and artificial intelligence (e.g., light-sensing and computer vision).

Dr. Ellis Monk

Dr. Ellis Monk

We’ve come a long way since the Gender Shades study, and nowadays transparency and anti-bias are key components of reputational cost for companies working with artificial intelligence. And unlike greenwashing opportunities for off-loading carbon to remote locations (and usually not verifiable by end users), AI bias is often times visible first-hand on user’s devices and apps we use everyday. To that extent, model cards–standard practice to “describe a model DNA”, including its performance, details on how it has been trained, what and how it should be used for–have started to include ethical considerations, including bias and geographical information, as well as fairness evaluation results. E.g., precision and recall metrics for face detection for model MediaPipe BlazeFace Short Range are reported across gender, skin tone and subregion.

At Onfido/Entrust, we’re doing something similar via our Building AI without bias whitepaper, and as we continue to ship new models to our customers. As part of our go/no-go decision to releasing a new model, we bake in several of these metrics.

Building AI without bias whitepaper by Onfido/Entrust

Building AI without bias whitepaper by Onfido/Entrust

We shouldn’t stick to skin tone as part of bias though. As hinted at by the Gender Shades study, the Google model cards and the Onfido/Entrust report above, other examples of biases in AI/ML systems include, but are not limited to: age, gender, geography, culture, race (not to be confused with skin tone), and other non-trivial dimensions relevant to your business, e.g., low-end vs. high-end devices, mobile device operating system and platform used (e.g., iOS, Android, Web browser).

Data, data, data

Data is crucial in the process of training the best, fairer models according to recommended practices of curating balanced datasets. Meta and Google are two of the companies pioneering here and putting their money where their mouth is, by open-sourcing datasets that directly contribute to a more just landscape of AI/ML development. With their release of the MST-E dataset and the Casual Conversations v2 dataset, both of these companies are doing their part to setting a higher bar for machine learning performance when it comes to diverse representation.

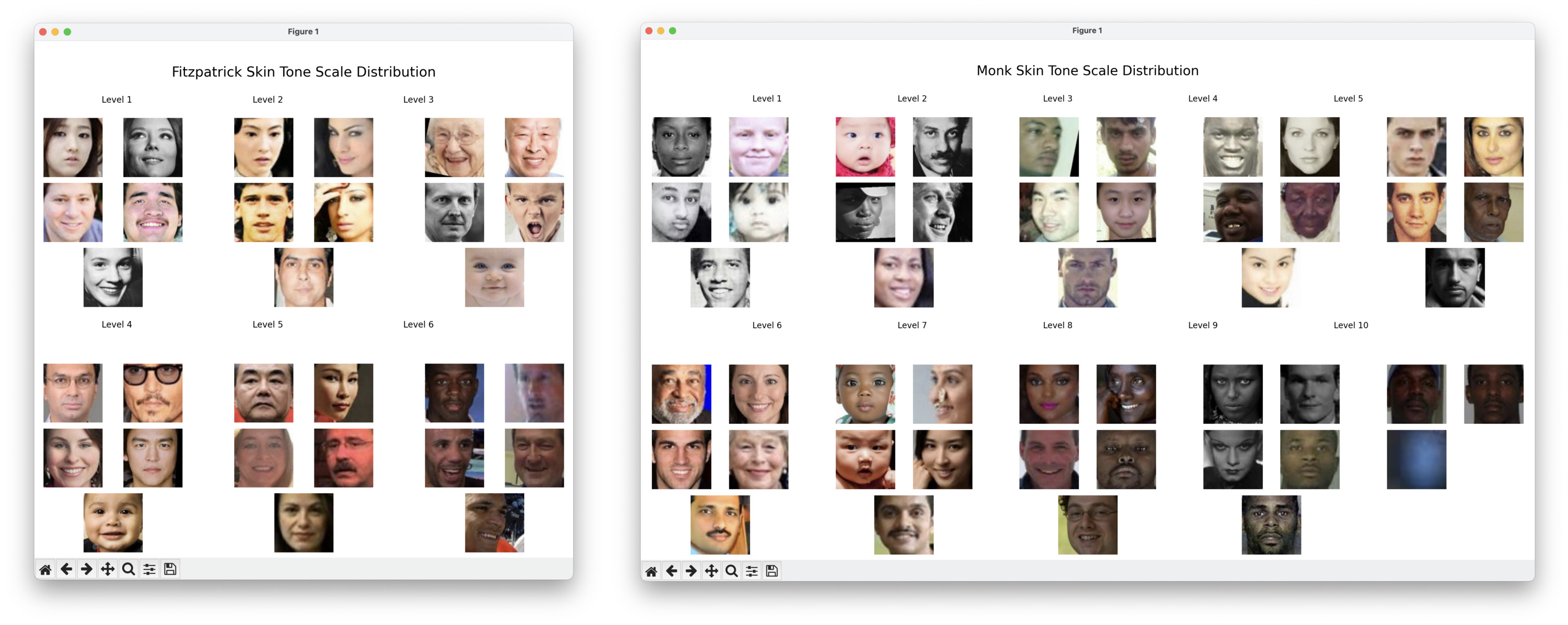

An example of a past dataset available in the wild is the UTKFace dataset from 2017, maintained by the University of Tennesse, Knoxville, USA. In it the differences in balancing between different skin tones is evident when comparing the Fitzpatrick scale to the Monk scale.

UTKFace dataset

UTKFace dataset

Using a script to approximate a person’s skin tone via the Monk Scale or Fitzpatrick Scale—by averaging color values to derive RGB representations with the help of the stone Python library—we quickly encounter issues with the Monk Scale, highlighting a lack of representation. For the Fitzpatrick Scale, identifying five faces per level is efficient, with the script completing in under a minute. However, with the Monk Scale, the process slows down dramatically, needing an escape hatch in the code to cap execution time at five minutes. This was tested on a standard M1 Mac with unoptimized, adapted Claude-generated code. And the escape hatch? It skips the need for finding the total of 5 required faces for skin tone 10. Exactly what you’d want to avoid in a real-world AI/ML training scenario.

Fitzpatrick vs. Monk scale samples on the UTKFace dataset

Fitzpatrick vs. Monk scale samples on the UTKFace dataset

You can also see various other issues with the approach. We did not ignore black and white images, and as such there are some matches for level 9 in the Monk scale that don’t make sense. Some additional mismatches on level 2. On the other hand, we can see the same black and white issue on the Fitzpatrick scale, but happening on levels 1 and 3, instead. Some pre-processing and additional cross-validation would be required to achieve production-grade data segmentation by considering a combination of, e.g., subregion, nationality, ethnicity.

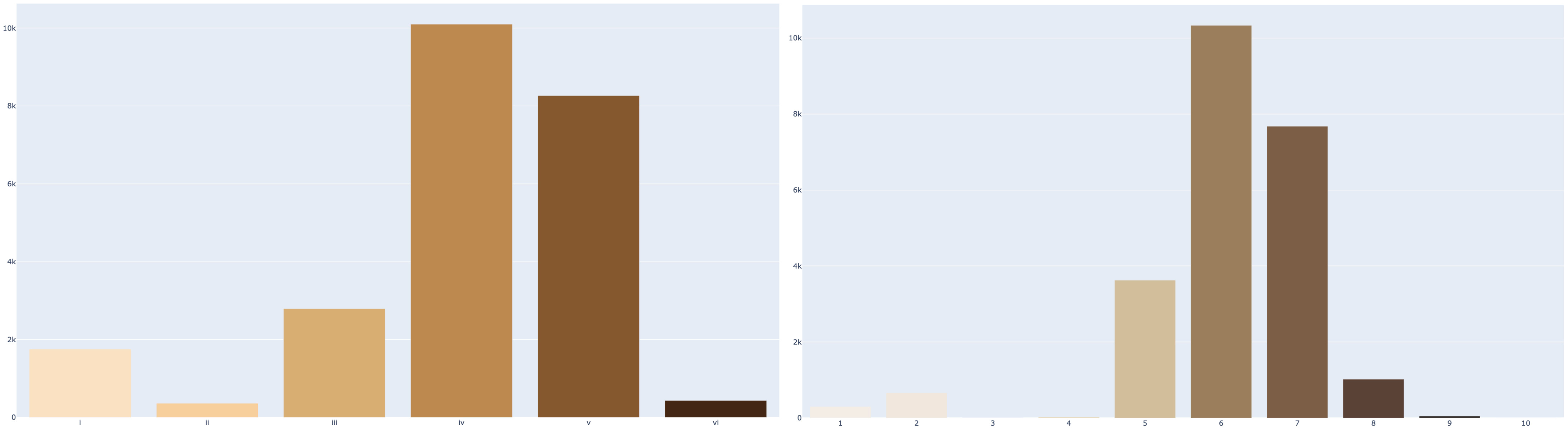

Plotting the bar charts for the ~23K data points in the UTKFace dataset for each of the skin tone scales under analysis yields the following:

Fitzpatrick vs. Monk scale bar chart on the UTKFace dataset

Fitzpatrick vs. Monk scale bar chart on the UTKFace dataset

As you can see, Monk Scale is making even more evident the under-representation of darker skin tone individuals in this dataset.

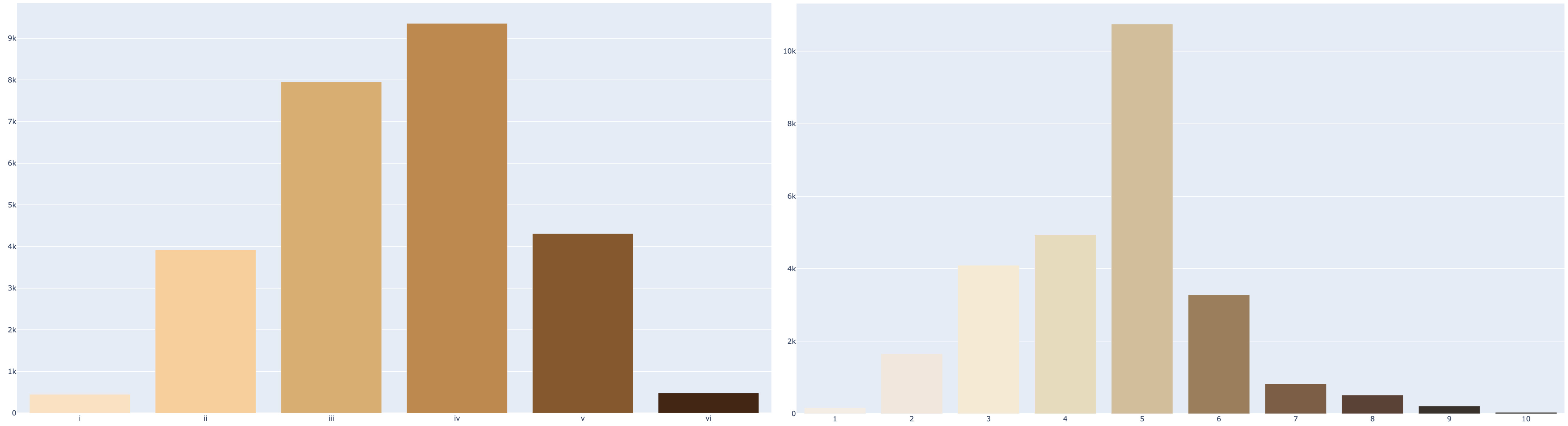

When analsing the Casual Conversations v2 dataset from Meta, one can observe a more bell-like curve typical of a normal distribution of skin tones. In absolute numbers though, we might get the feeling arguably more needs to be done.

Fitzpatrick vs. Monk scale bar chart on the Casual Conversations v2 dataset

Fitzpatrick vs. Monk scale bar chart on the Casual Conversations v2 dataset

In the aforementioned UTKFace dataset, we had ~0.01% of representation for individuals of the darkest skin pigment. In the Casual Conversations v2 dataset that goes to ~0.14%, i.e., not much better. Is this representative of the world population? I’m not sure, but a quick Perplexity search seems to point not. Even if so, we know population-like stratification might not suffice in making algorithms fair and unbiased, since neural nets are very data hungry.

But you shouldn’t think this is the end of it and that companies are giving up. Indeed these datasets only form the basis of discussion and examples of best practices and recommendations. It is up to all of us in the AI/ML space to make the best out of pre-processing and training stages, incorporating these best practices and making sure our proprietary datasets, the ones our specific models feed off of, often times with millions more data points and terabytes (or even petabytes) of data, are well balanced. And we should make sure we have the proper guard-rails in place to make incremental releases with ever-improving levels of fairness and anti-bias.

Races have never existed in nature. They were formulated by people who had opinions and very few facts.

In the 70s, Dr. Fitzpatrick was studying the effects of PUVA on different human skin tones, particularly white skin. Its eurocentricity lead to constructive and well-placed criticism. Today, we continue to face data imbalance issues in dermatology research:

Machine learning will likely play a key role in the future of dermatology. Diligence and transparency are needed to prevent new health care disparities in patients with skin of color.

We’ll have to continue to adapt our data science best practices in order to guarantee we rip the benefits of the tidal wave of artificial intelligence, from financial services to transportation, law, energy, scientific research, medicine and many other verticals.

We keep pushing.