Another year, another edition of PixelsCamp (formerly, SAPO Codebits). And this year, I was fortunate enough to not only attend it, but also present a talk. Giving back to the community is something one should do, if only from time to time. Either be it by blog posts, open source projects or talks such as this one. And it all went very well for my first time on stage. Lots of familiar faces in the front rows helped, of course. My teammates from Onfido and friends from Talkdesk showed up to cheer for me. And it felt amazing!

Since at Onfido we’ve been deploying lots of microservices, and the team I am in was responsible for two of those critical services that were extracted from our existing monolith, I thought about doing a talk highlighting some of our internal best practices, architectural choices we made and design alternatives.

So here am I, trying to give back a little bit more. You can see the slides and read the transcript for my talk below. I hope it’s as interesting to you as it was for me to do it.

Startups used to start out in garages. We’ve all heard about the stories of Apple or Hewlett-Packard.

Technology-driven startups don’t need to own big server racks anymore. God, I don’t even know what this is. Sorry.

We write and deploy code easily using a laptop from wherever. Programming languages and web frameworks have gotten easier to use throughout the years. We can get a lot done with less code.

But most importantly we can do it badly, too.

When running a startup, achieving the MVP is one of the first steps in terms of development. You want to do it fast. And you want it to do exactly what you designed it for. Not more, not less. It’s targeted. Specific. Limited.

But that’s often not all we want. If everything goes well, we start to evolve it. We may pivot from the initial idea. We will eventually add more and more features. Hopefully, the engineering team will grow.

And that’s when the problems start to arise.

My name is Daniel Serrano. I’m a software engineer at Onfido. Previously, I was a software engineer at Talkdesk, and before that I was a software engineering intern at Hole19. I hold a Master’s degree in Computer Science from Instituto Superior Técnico, here in Lisbon. Shout out to Técnico.

In this talk I’m going to give insights into how you can achieve a successful transition from a monolith-based architecture to a microservices-oriented one. We’ll go through some of the general guidelines and patterns that have helped us at Onfido, and look at some specific architecture choices available when deciding to extract microservices out of your existing monolith.

So first, what is Onfido, and what did the system look like when I joined the company? Onfido is a background checks company, so that means criminal, identity, driving record checks. Basically we know what you did last summer.

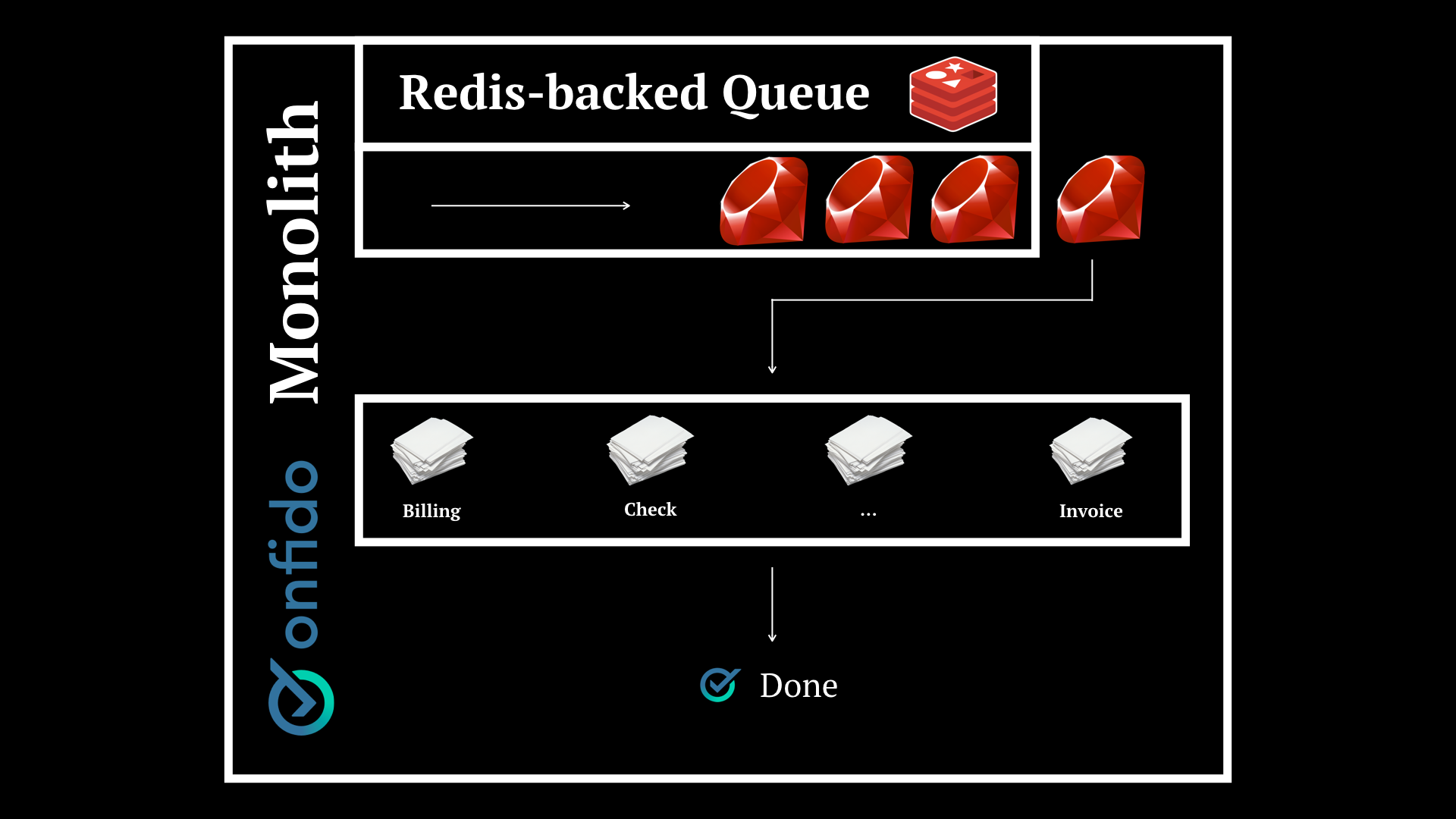

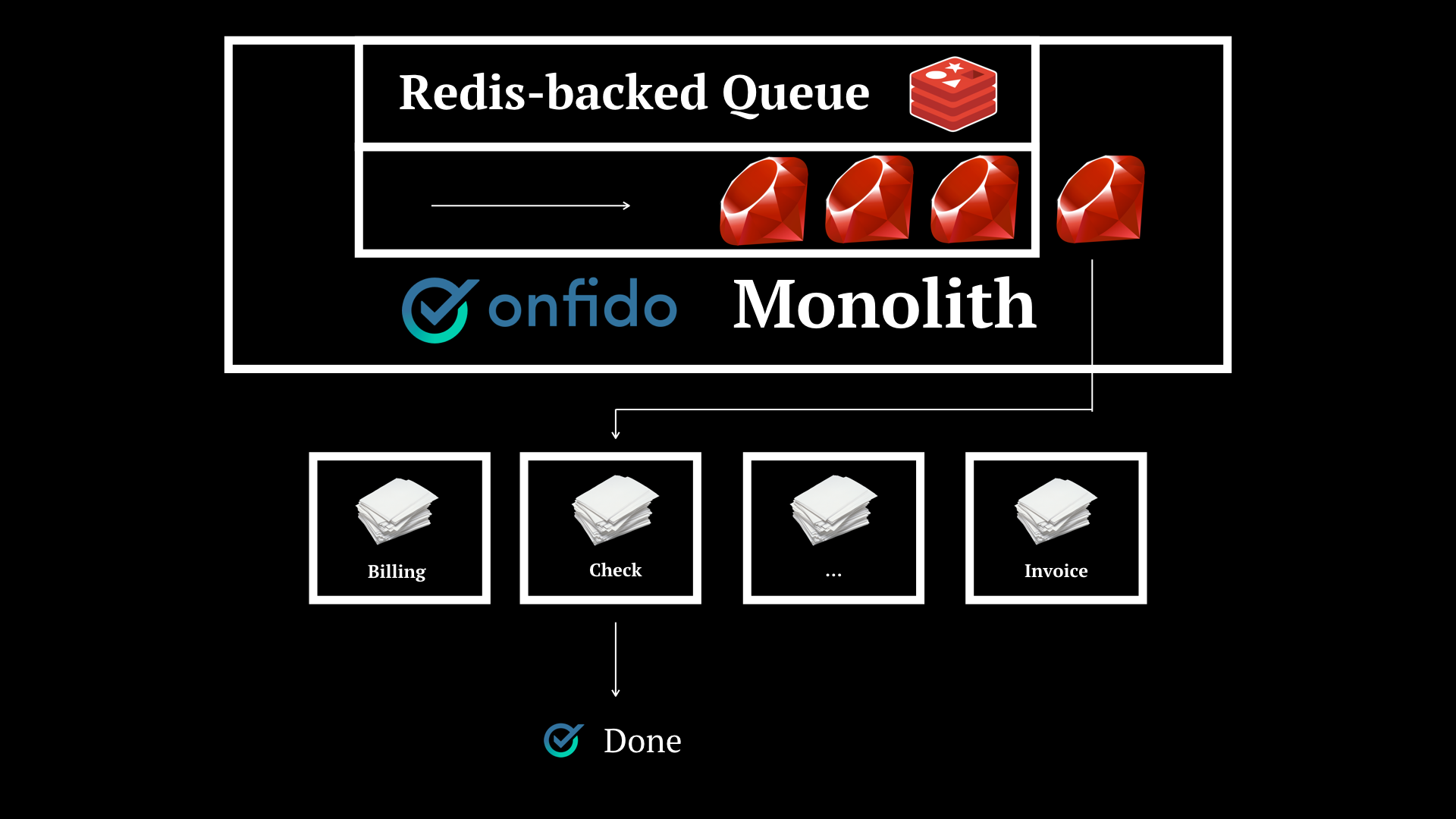

When I joined, we had a system that looked like this. A monolith with a Redis-backed queue that would take on tasks and use specific logic to handle each job.

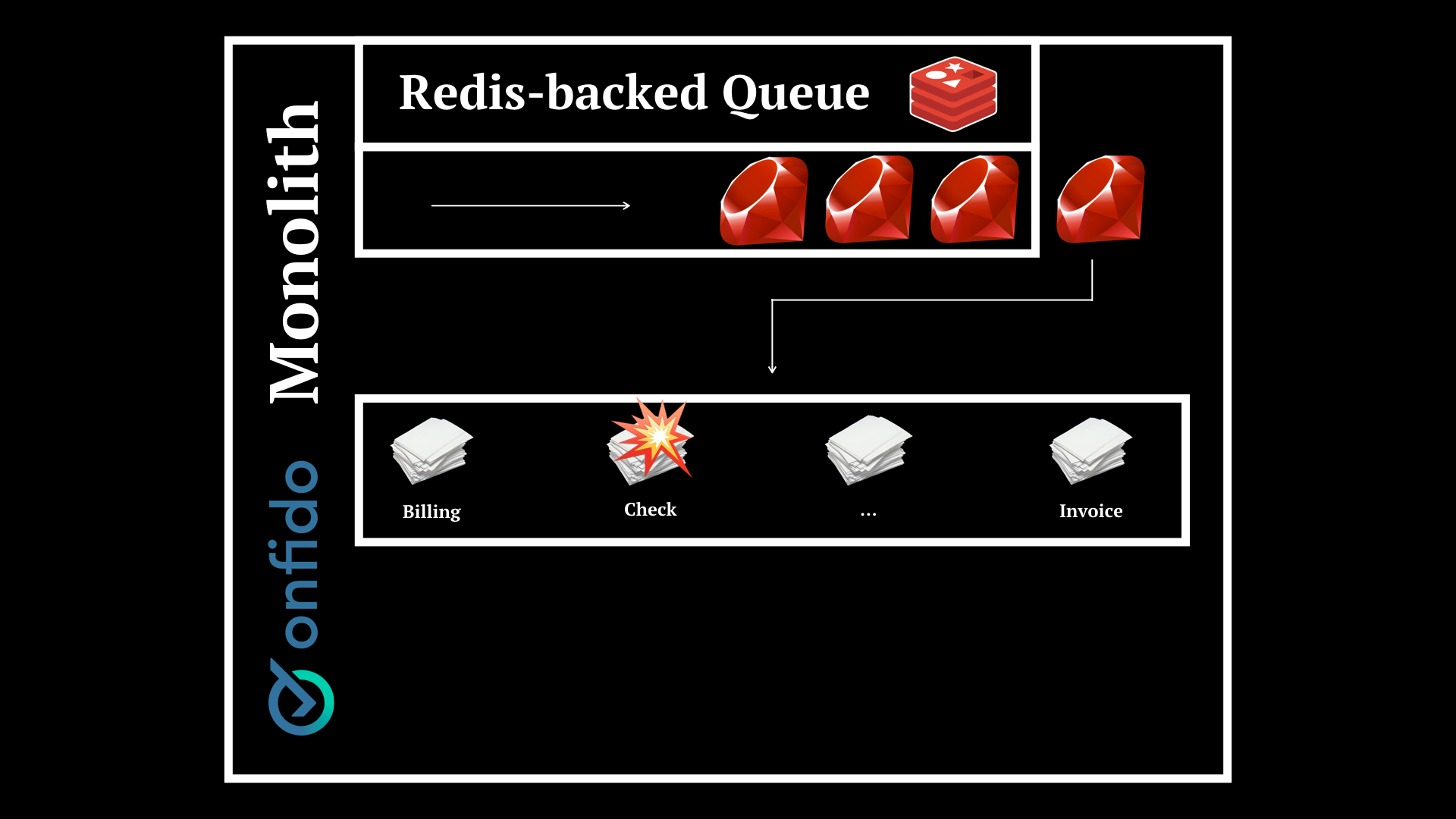

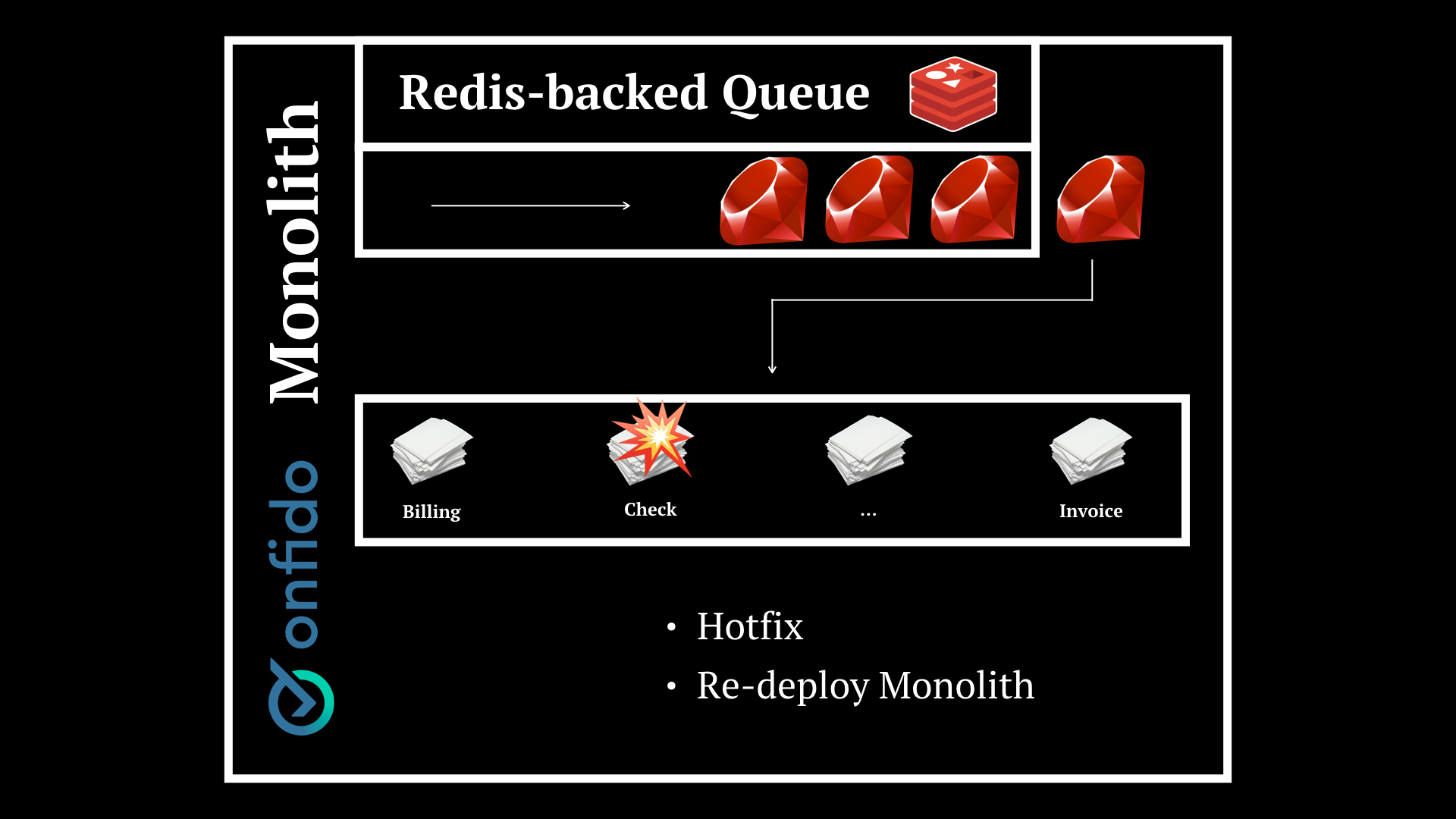

This obviously poses problems. Imagine one of the modules with specific logic fails. Say we have Billing, Check and Invoice services and a bug is causing checks to fail.

You will have to issue an hotfix and re-deploy the whole thing. There is no granularity.

We’re tied to the slow monolith pipeline steps, the separation of concerns could be better thought of, and also teams should be focused in finer-grained (complex enough) parts of the system.

Let’s turn to the masters to understand the concept of microservices. James Lewis and Martin Fowler wrote it better.

So, this is what we want to achieve. A microservices-oriented alternative in which each part of the system is abstracted away into its own microservice.

I’m going to try and give you guys a little bit of insight into how we did it, some of the lessons learned and future paths we want to explore.

And we start out by this concept Sam Newman presents in his book “Building Microservices”, about how you should have what he calls a “Required Standard”. The “Flanders web app”, if you will. The one that you will use to look at and cross off items as you build your new microservice. So this is kind of our “Required Standard”.

One of the things we introduced as part of the microservices direction we were taking as a company was we introduced RFCs. I’m talking about these sort of RFCs. Ours should be concise as well, and they should give some room for discussion. People can comment on it and suggest improvements. This has helped us numerous times, by having DevOps and Security pitch in with invaluable insights, to people with experience with a given technology weighing in about the best approach to a problem. Usually, these “a-ha” moments happen across teams. With an RFC, we have a document we can share and “pass around”. And because it is written down, entropy in the form of misinterpretation is reduced.

Feature parity is another thing to take into account when you start to extract functionality from your existing monolith to a separate microservice. You will have to ensure what you are developing in either of them gets replicated on the other side too. Otherwise, you might end-up with different functionality which may not be desired. In the beginning we need to have a direction, a path, and that path is feature parity. In our case though, we added functionality in one of our microservices and did not care about the monolith because we were turning on the usage of that microservice for everyone in a matter of days. The monolith would effectively be deprecated. YMMV.

Use feature flags. They help you do more confident rollouts. At the entry point in your code where you might call your new microservice, do it only conditionally. If the feature flag is active, route the request to your microservice. Otherwise, just run the old code. Beta clients of your microservice will help you to smooth out the rough edges of your app. You minimise risk and incrementally increase robustness. When all traffic is going through the microservice you can start to think about deprecating the old code and feature pairity may no longer be a concern.

This is what you’re after when you start thinking about splitting your monolith. The entry point. Once you find it, you can start extracting. In our case it was easy — the moment of selecting a worker to process the enqueued work we either used an HTTP worker that would call the microservice, or ran the old code.

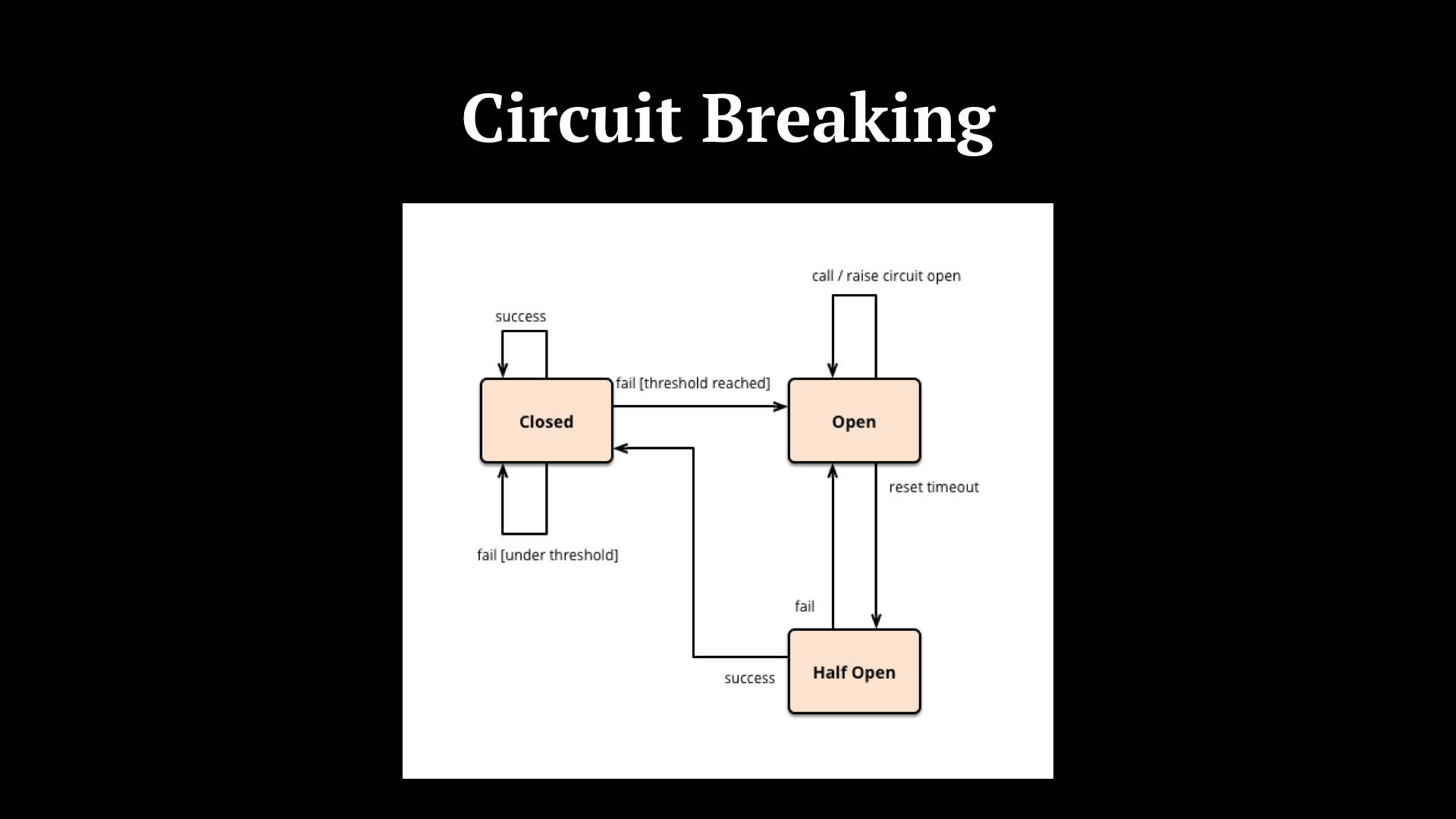

With every call to a microservice, there is risk. In distributed system, we call being resilient to risk “fault tolerance”. Michael Nygard coined the term Circuit Breaker in his book Release It! When contacting external services, which in your microservice architecture might be other (internal) microservices in your app ecosystem, we keep a count of the number of failures we get and if it reaches a certain threshold we open the circuit, meaning we halt requests for a specified amount of time.

After some time, we try again. That’s the Half Open state. If it fails again, we’re back to Open. Otherwise, if the microservice is back up, we close the circuit and communication with the external service is re-established. In this way you avoid exhausting resources in dead-ends, request queueing is reduced and the unresponsive services won’t get overloaded. Examples of implementations include Netflix’s Hystrix in Java, Stoplight in Ruby or Fuse in Erlang.

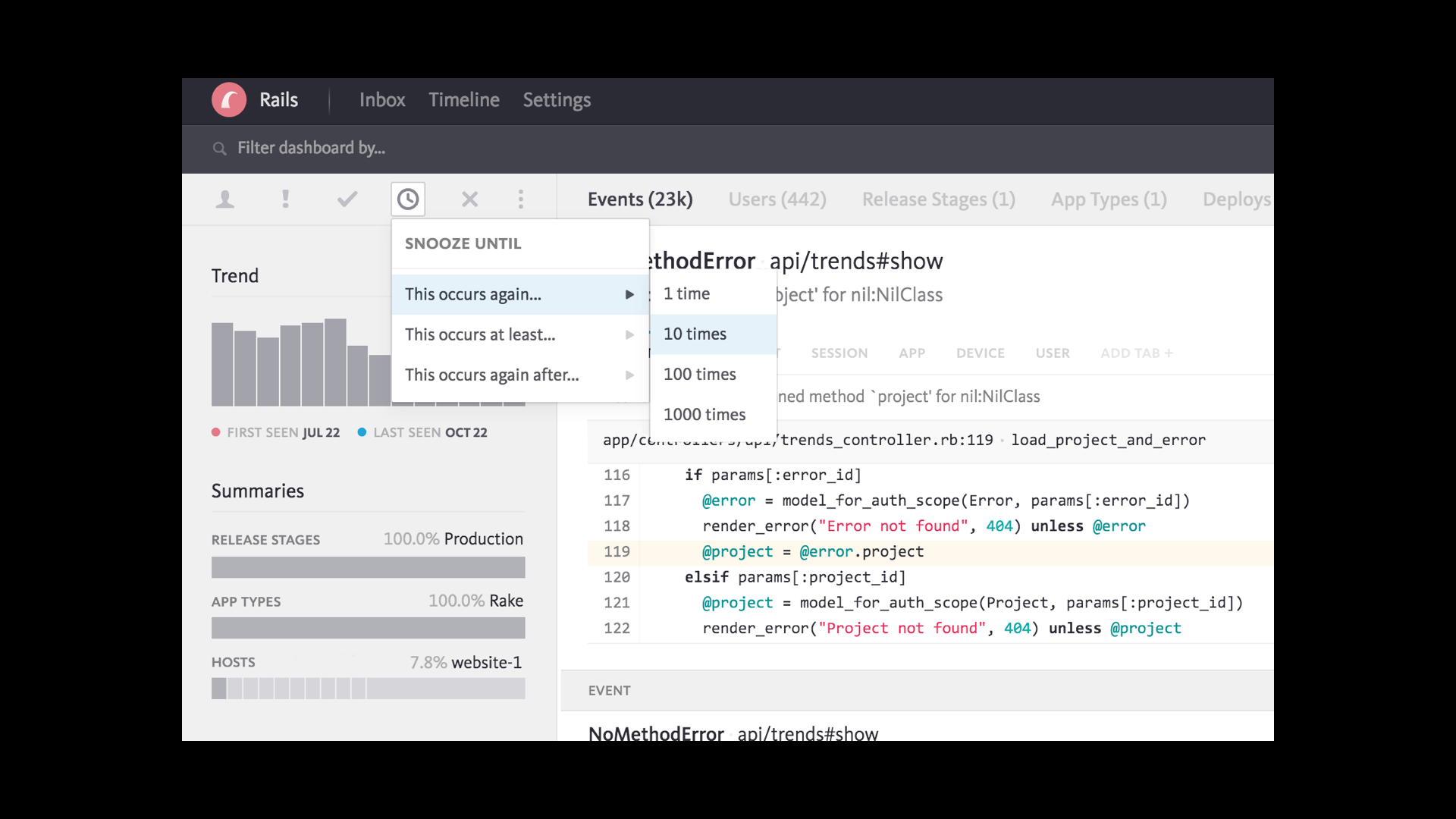

But you know… your system will still fail. And that’s fine. Most of the times. You should just have a plan in place in case something happens. You will want to know when errors happened, what caused them and what you can do prevent them from happening again.

At Onfido, like I’m sure most of you here, we use an error tracking service that provides us with the file, line and context of a given error. Example of such services include Airbrake, Bugsnag and Sentry. Don’t panic if your morning routine starts out with a coffee and a review of yesterday night’s errors. Paranoid monitoring is no reason to be ashamed when extracting microservices.

Logs are relevant for “archeological debugging”-type digging. You find out an error has been happening for the last 3 days but hasn’t been reported to your error tracking mechanism. You end up finding out that it had happened before, about a month ago.

What we did at Onfido was we used logs as a way to predict the future. We deployed to production a microservice that acted as a validation module and, incurring in an acceptable overhead, we feature flagged (for some users) a call to it before we ran the old code… not instead. This allowed us to log what the result would have been if we had processed the request via the microservice. We could see the actual and “would be” outcomes in the logs, and evaluate the results.

Again, as I’m sure most of you do, we use a log management service to access our logs. Some examples are Loggly, SumoLogic or LogEntries. Or just build your own ELK stack, I hear that’s popular these days.

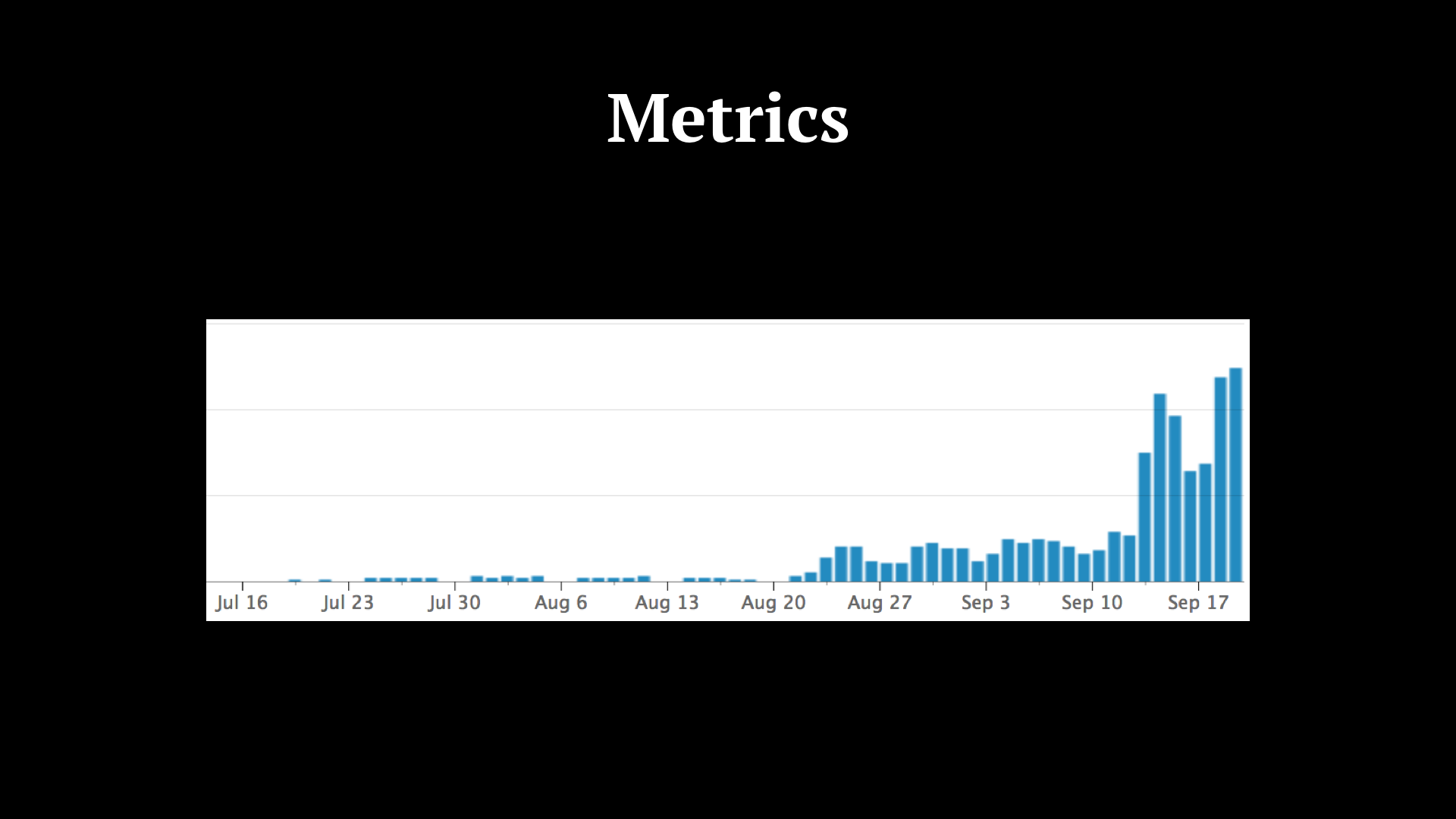

Metrics are also important, as in every other app. In microservices though, they will help you better understand and correlate events. For instance, if you notice your monolith is unhealthy and one of your microservices is behaving abnormally there is likely a connection. By setting up alerts, you can also have more rapid reaction to problems.

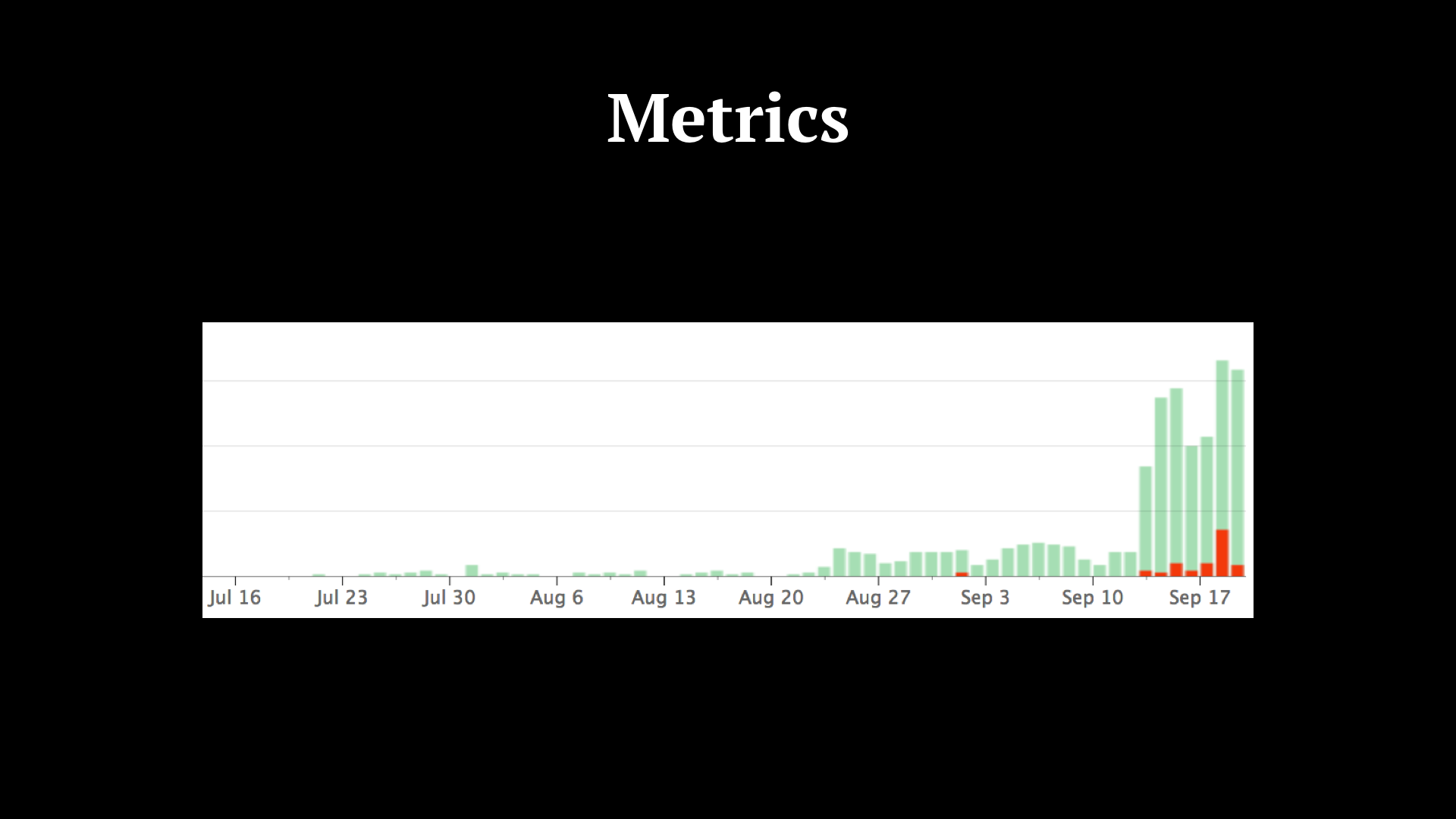

This is a requests load graph of one of our microservices. As you can see, we started out by doing requests on our own, internally, within the members of the team. By August 20th we started to route some requests to the microservice and by mid-September we activated it for everyone.

This one is an error ratio graph. In red, you can see we had a bit of a rough day around the 17th.

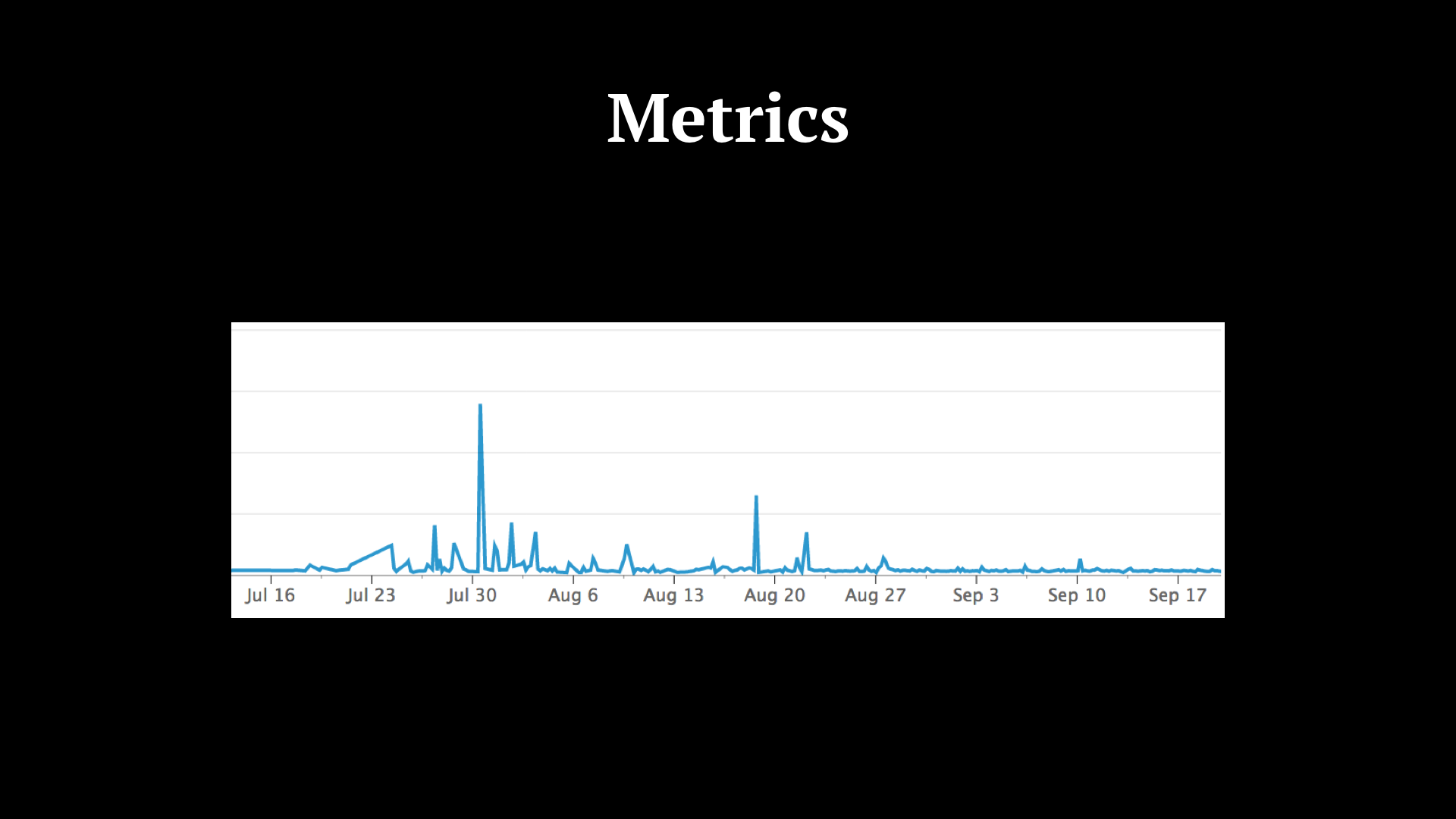

Here, a graph of the average response times of another microservice we called from this one here. Don’t ask me what happened on July 30th.

But I also wanted to take this opportunity to give a brief overview of some of the design decisions and alternatives you can choose from when setting up a microservices-oriented architecture.

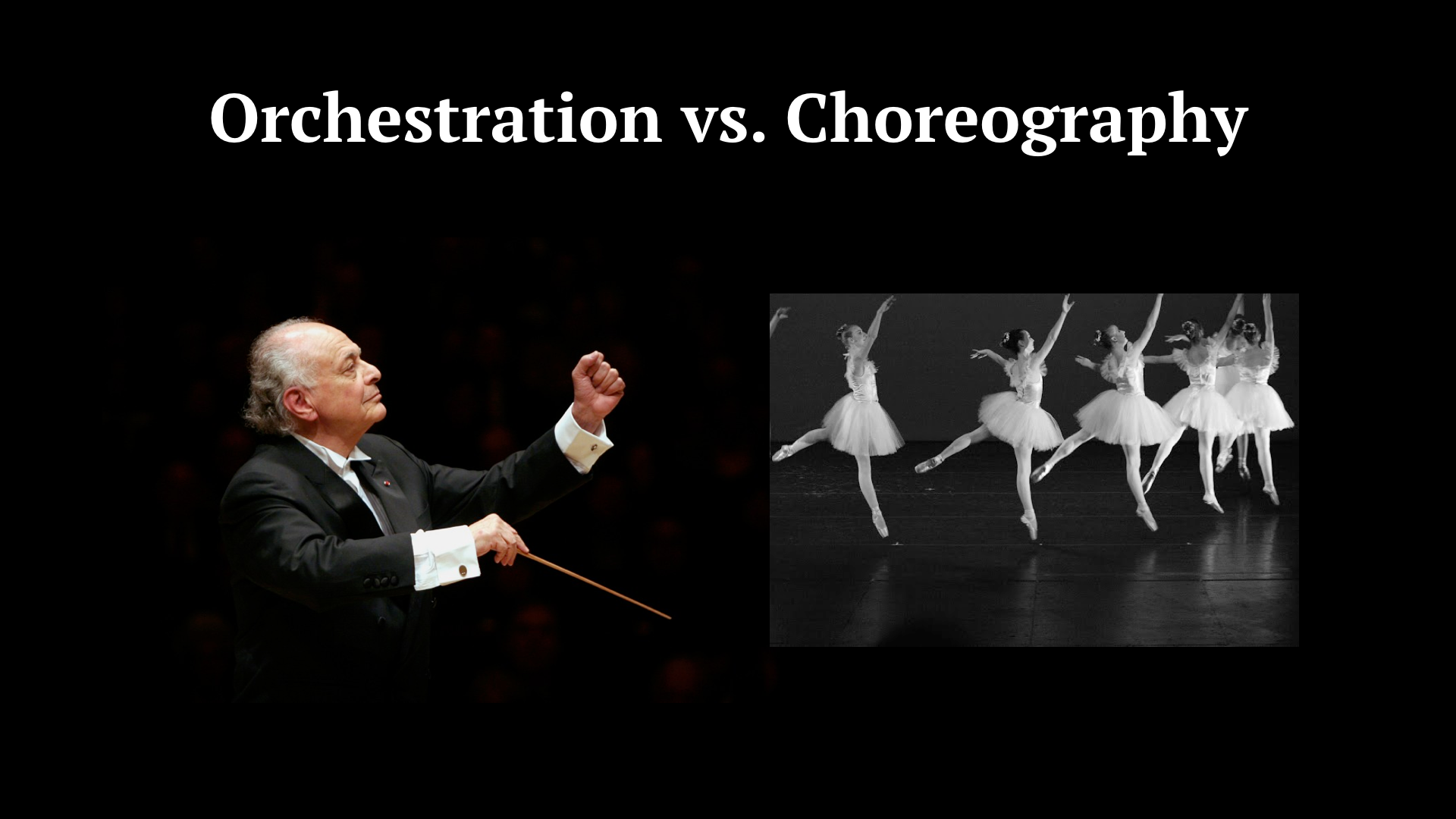

One of the biggest decisions you can make when setting up a new microservice (or a set of multiple microservices) is to choose between orchestration and choreography. Authority and autonomy. This difference will be reflected in the way your services communicate with one another. Orchestration is better suited at use cases in which logic is contained, not spread out or overreaching (e.g., routing requests to a service for async processing). Choreography implies an event-driven architecture, ideal for systems whose consequences are disparate (e.g., you must send out an e-mail, SMS and notify mobile app when user changes password).

Shared DB is, at best, a tolerable anti-pattern. I’ve worked in a production system that used this approach. It entails multiple microservices accessing the same DB cluster. It has problems in that you are tied to the existing schema. And in every other service you will be able to easily (and dangerously) dilute the thin line that separates the concerns of the different services. At Onfido, we have a single system responsible for updating the DB. Other services only provide data.

You can pass around information in two ways when communicating between microservices. You either are descriptive and pass all information the microservice needs to perform a given task (e.g., user’s first name, last name and e-mail), risking it not being fresh. Or you can instead rely on the user’s unique ID (your reference) to, at the microservice level, fetch the latest information it needs (first, last name and e-mail). With access by reference load on services used to fetch information might be too great.

Follow KISS. Keep it simple, stupid. Protocols of communication should avoid technology coupling (e.g., RPC via Java RMI ties consumer and producer to the JVM). Thrift and protocol buffers have major support. At Onfido we sticked with JSON over HTTP.

So, this is it. The dos and don’ts as we see them, and how they’ve worked for us. These are the things that have allowed us to scale our engineering team while keeping our customers happy. Now I want to look at some of the things we’re either thinking about for the near future or actively working on already.

We want to experiment with distributed tracing systems. Google’s Dapper, Twitter’s Zipkin and Uber’s Jaeger are examples of such systems. In order to have the holistic view of your complex distributed system, logs and metrics per-service won’t cut it. Distributed traces allow you to do root cause analysis, identify bottlenecks and with that devise optimisation strategies for your services.

API Gateway. Microservices typically offer fine-grained APIs, causing clients to have to fetch information from multiple co-existing services. An API Gateway is the façade hiding the complexities of the underlying system made up of a mesh of microservices. Authentication, authorisation and rate limiting can be implemented in the API Gateway. Netflix’s Zuul, Amazon’s API Gateway and Kong can be used to implement your solution.

The end.

Until next year, PixelsCamp!